Learn how the JavaScript “this” keyword differs when instantiating a constructor (as opposed to executing the function).

Learn how the JavaScript “this” keyword differs when instantiating a constructor (as opposed to executing the function).

In earlier articles of the “The JavaScript “this” Keyword Deep Dive” series, we discussed how the meaning of “this” differs in various scenarios. In this article, we will focus on JavaScript constructors. It is critical to keep in mind that in JavaScript, constructor functions act like classes. They allow you to define an object that could exist. The constructor itself is not yet an object. When we instantiate that constructor, the return value of the instantiation will be an object, and in that object, “this” refers to the instance object itself.

So, inside of a constructor function, the JavaScript keyword refers to the object that will be created when that constructor is instantiated.

Example # 1

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

window.music = 'classical'; window.getMusic = function(){ return this.music; }; var Foo = function(){ this.music = "jazz"; this.getMusic = function(){ return this.music; } } var bar = new Foo(); console.log(this.getMusic()); // 'classical' (global) console.log(bar.getMusic()); // 'jazz' (property of bar, which is an instance of Foo) |

In Example #1, you’ll see that we have created two new properties of the window object: “music” and “getMusic”. The “window.getMusic” method returns the value of window.music, but it does so by referencing: “this.music”. Since the “window.getMusic” method is executed in the global context, the JavaScript “this” keyword refers to the window object, which is why window.getMusic returns “classical”.

When you instantiate a JavaScript constructor function, the JavaScript “this” keyword refers to the instance of the constructor.

We’ve also created a constructor function named “Foo”. When we instantiate Foo, we assign that instantiation to the variable: “bar”. In other words, the variable “bar” becomes an instance of “Foo”. This is a very important point.

When you instantiate a JavaScript constructor function, the JavaScript “this” keyword refers to the instance of the constructor. If you remember from previous articles, constructor functions act like classes, allowing you to define a “blueprint” object, and then create “instances” of that “class”. The “instances” are JavaScript objects, but they differ from object literals in a few ways.

For an in-depth discussion of the difference between an object literal and an instance object, see the article: “What is the difference between an Object Literal and an Instance Object in JavaScript? | Kevin Chisholm – Blog”.

Earlier on, we established that inside a function that is not a method, the JavaScript “this” keyword refers to the window object. If you truly want to understand constructor functions, it is important to remember how the JavaScript “this” keyword differs inside that constructor. When you look at the code, it seems as if “this” will refer to the window object. If we were to simply execute Foo as if it were a normal function, this would be true (and we will discuss this scenario in Example # 3). But we don’t simply execute Foo; we instantiate it: var bar = new Foo().

When you instantiate a JavaScript constructor function, an object is returned. The JavaScript “this” keyword has a special meaning inside of that object: it refers to itself. In other words, when you create your constructor function, you can use the “this” keyword to reference the object that WILL be created when the constructor is instantiated.

So, in Example # 1, the getMusic method returns “this.music”. Since the “music” property of Foo is: “jazz”, then the getMethod returns “jazz”. When we instantiate Foo, the variable “bar” becomes an instance of Foo, so bar.getMusic() returns “jazz”.

HERE IS THE JS-FIDDLE.NET LINK FOR EXAMPLE # 1: http://jsfiddle.net/2RFa3/

Example # 2

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

window.music = 'classical'; window.getMusic = function(){ return this.music; }; var Foo = function(){ this.music = "jazz"; this.getMusic = function(){ var myFunction = function(){ return this.music; } return myFunction(); } } var bar = new Foo(); console.log(bar.getMusic()); // 'classical' (global) |

In Example # 2, we have changed Foo’s “GetMusic” method. Instead of returning “this.music”, it returns an executed function. While at first glance, it may seem as though the “getMusic” method will return “jazz”, the JSFiddle.net link demonstrates that this is not the case.

Inside of the “getMusic” method, we have defined a variable that is equal to an anonymous function: “myFunction”. Here is where things get a bit tricky: “myFunction” is not a method. So, inside that function, the JavaScript “this” keyword refers to the window object. As a result, that function returns “classical” because inside of “myFunction”, this.music is the same thing as window.music, and window.music is “classical”.

HERE IS THE JS-FIDDLE.NET LINK FOR EXAMPLE # 2: http://jsfiddle.net/2RFa3/1/

Example # 3

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

window.music = 'classical'; window.getMusic = function(){ return this.music; }; var Foo = function(){ this.music = "jazz"; this.getMusic = function(){ return this.music; } } console.log(this.getMusic()); // 'classical' (global) Foo(); // by executing Foo, we inadvertently overwrite window.music and window.getMusic. this is bad console.log(this.getMusic()); // 'jazz' (new global) |

In Example # 3, we have an example of a scenario that you don’t want: executing a JavaScript constructor function instead of instantiating it. Hopefully, this is a mistake that you will catch quickly, but it can happen. It is also possible that you might inherit code that contains such a bug. Either way, this is bad.

While the Foo constructor still has a “getMusic” method, because we execute Foo, instead of instantiating it, the code inside of Foo overwrites two properties that we created earlier: window.music and window.getMusic. As a result, when we output the value of “this.getMusic()”, we get “jazz”, because when we executed Foo, we overwrote window.music, changing it from “classical” to “jazz”.

While this is a pattern that you want to be sure to avoid in your code, it is important that you be able to spot it. This kind of bug can leave you pulling your hair out for hours.

HERE IS THE JS-FIDDLE.NET LINK FOR EXAMPLE # 3: http://jsfiddle.net/2RFa3/2/

Summary

In this article we learned how the JavaScript “this” keyword behaves in a constructor function. We learned about instantiating a constructor and the relationship between “this” and the instance object. We also discussed a couple of scenarios that are important to understand with regards to “this” and constructor functions.

Depending on the scenario, the JavaScript “this” keyword may refer to the object of which the method is a property, or the window object.

Depending on the scenario, the JavaScript “this” keyword may refer to the object of which the method is a property, or the window object. If you are just getting started with server-side JavaScript, “Node for Front-End Developers” offers a fast, high-quality introduction.

If you are just getting started with server-side JavaScript, “Node for Front-End Developers” offers a fast, high-quality introduction.

A popular saying in the Real Estate business is: “Location, location, location!” Well, in JavaScript, it’s all about “context”. When you want to leverage the very powerful keyword: “this”, then understanding the current context is critical.

A popular saying in the Real Estate business is: “Location, location, location!” Well, in JavaScript, it’s all about “context”. When you want to leverage the very powerful keyword: “this”, then understanding the current context is critical. Combine multiple JS files into one using JavaScript, Node.js and Grunt.

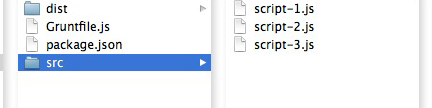

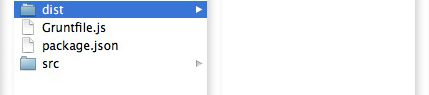

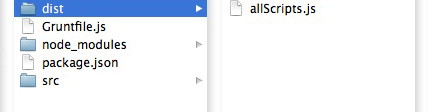

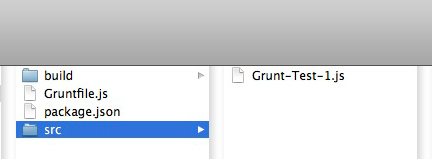

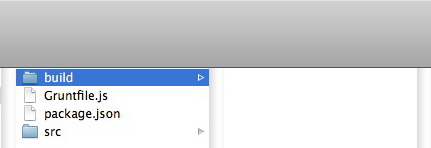

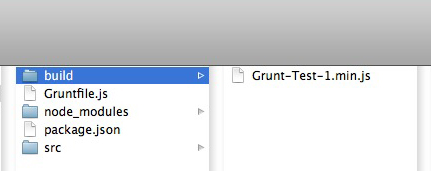

Combine multiple JS files into one using JavaScript, Node.js and Grunt.

By leveraging the Node.js middleware “express”, we can create functionality for viewing, adding or deleting JSON data.

By leveraging the Node.js middleware “express”, we can create functionality for viewing, adding or deleting JSON data. Adding an event listener to your map is much like using the addEventListener() method on a DOM element.

Adding an event listener to your map is much like using the addEventListener() method on a DOM element.

What happens when your JavaScript code depends on not only multiple asynchronous scripts, but also one or more JSONP calls? Once again, jQuery.Deferred() and jQuery.when() save the day.

What happens when your JavaScript code depends on not only multiple asynchronous scripts, but also one or more JSONP calls? Once again, jQuery.Deferred() and jQuery.when() save the day.