The jQuery.when() method allows you to treat multiple asynchronous script calls as one logical event. But what if there is a chance that one or more dependencies are already loaded?

The jQuery.when() method allows you to treat multiple asynchronous script calls as one logical event. But what if there is a chance that one or more dependencies are already loaded?

I just completed a project for a client that involved some tricky script loading logic. I had to use a jQuery plugin and icanhaz.js for templating (I prefer Mustache.js, but the previous developer had implemented icanhaz.js in many of the site’s templates). Now the difficult thing was that I had already written some JavaScript code that lazy-loads touts in the main navigation bar, which appears on every page in the site. So, the situation in hand was as follows:

- My JavaScript depends on icanhaz.js and a jQuery plugin

- icanhaz.js is asynchronously loaded further up the page

- Since icanhaz.js is loaded asynchronously, I can’t assume it’s loaded when my new code runs

- I don’t want to load icanhaz.js twice

eeesh….

I knew I could count on the jQuery.when() method to handle the multiple asynchronous script loads. Specifically, jQuery.when() can treat two or more asynchronous script load events as one event. The completion of the multiple events can represent one completed event, which can be used to tell the rest of your code: “hey, we have what we need, let’s proceed.” But at first I was not sure how to abstract the details of whether or not a script is already loaded. For example, If icanhaz.js has already been loaded in the page, I don’t want to waste time by loading it again (and potentially cause unexpected behavior because it loaded twice).

So I decided to leverage the jQuery.deferred constructor.

In short, for each script that needed to be loaded (i.e. each dependency), I wrote a function that checks to see if that script was already loaded. If so, then the function returns a resolved jQuery.deferred instance. If not, then I simply use the jQuery.when() method to wrap a jQuery.getScript() call, which returns an unresolved jQuery.deferred instance. So either way, my function returns a jQuery.deferred instance. This is perfect because jQuery can easily understand (and act upon) the “state” of a jQuery.deferred instance. And most importantly, jQuery can view multiple jQuery.deferred instances as one “event”.

“…..hmmmm Idunno Kevin, this is all starting to sound a little convoluted to me!”

I had similar feelings when I was working this out in my head. But once I fired up my JavaScript console, and started testing the code, it was not only easy to understand the logic, it worked flawlessly (serious kudos to the jQuery folks; these are awesome features).

So, for this article, I decided to use Mustache.js and the jQuery validation plugin as my dependencies. Mustache.js will be used to build the form and the jQuery validation plugin will provide form validation.

Example # 1

|

|

<div id="container"> <h1>jQuery.when() Method Example</h1> <h2>Multiple script dependency management</h2> </div> |

In Example # 1, we simply have the markup for the page. Not too much going on here: a page wrapper and two header elements. What it does illustrate is that the form and the validation you see when you run the final working example is all handled by our two dependencies: Mustache.js and the jQuery form validation plugin.

Example # 2

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

var mustacheJsUrl = 'https://raw.github.com/janl/mustache.js/master/mustache.js', jqformValUrl = 'https://raw.github.com/sdellow/jQuery-Form-Validation/master/jquery.form-validation.js', data = { fieldName: "first_name", label: "First Name", submit: "Submit this form", error: "Please be sure to enter your first name" }, template = '' + '<form id="testform">' + '<div class="field">' + '<label for="{{fieldName}}">{{label}}</label>' + '<input type="text" id="{{fieldName}}" name="{{fieldName}}" class="required">' + '<button type="submit">{{submit}}</button>' + '<div class="val-message">{{error}}</div>' + '</div>' + '</form>'; |

Now, in Example # 2, we have provided two constants which are simply the URLs for the script calls that we (might) have to make. This is a pattern that I like to follow, which can help to minimize clutter in your implementation code; make values that will never change constants and put them all in one coherent place.

The variable “data” simply holds an object literal that will be used by Mustache.js to populate the template, and the variable “template” is the string used by Mustache.js to create the template. (Notice the values inside of the double curly brackets: “{{}}”; these all map to properties in the “data” object.)

Example # 3

|

|

var confirmMustacheJs = function (){ //is mustache.js loaded on this page? if(!window.Mustache || !window.Mustache || !window.Mustache.name === 'mustache.js'){ //if not, load it return $.when($.getScript(mustacheJsUrl)); } else { //it's loaded, just return the resolved jQuery deferred object console.log('Mustache is already loaded...'); return jQuery.Deferred().resolve(); }; } |

In Example # 3, we have a function that always returns a jQuery.deferred instance. The if/else statement provides two possible outcomes: Mustache.js is already loaded in the page or Mustache.js is not loaded. We test for the existence of window.Mustache (and the value of its “name” property) in order to determine the answer. If Mustache.js is already loaded, then we simply return a resolved jQuery.deferred object. If it is not, we then return a call to jQuery.when(), passing a jQuery.getScript() call as an argument. The jQuery.when method returns a jQuery.deferred instance that is in an “unresolved” state until the getScript() call completes.

The key point here is that even though in this case our function returns an un-resolved jQuery.deferred instance, the fact that it is a jQuery.deferred object is all we need.

So there is no need to walk through the function that does the same thing for the jQuery validation plugin; the logic is exactly the same. If you look at the code for the full working example at the end of this article, you’ll see that the only difference is the URL for the script that is loaded, and the way in which we determine if the plugin exists (i.e. we check for the existence of a property of the jQuery.prototype object named “formval”).

Example # 4

|

|

var formValIsLoaded = confirmFormVal(), mustacheIsLoaded = confirmMustacheJs(); |

Now here in Example # 4, we create two variables. Both variables become a jQuery.deferred object because in each case, the variable is being set to the return value of the methods we just discussed in Example # 3: each of these methods returns a jQuery.deferred object. Again, these objects are in either a “pending” or “resolved” state, depending on whether or not the specified script was loaded.

Example # 5

|

|

$.when(formValIsLoaded,mustacheIsLoaded).done(function() |

{ //build the markup fom the template (uses Mustache.js) var form = Mustache.render(template,data); //inject the form $(‘#container’).append(form); //setup the form for validation (form validation plugin) $(‘#testform’).formval(); });

In Example # 5, look very closely at the first line: $.when(formValIsLoaded,mustacheIsLoaded). Essentially, this line says: “When the two arguments resolve…” that is, when both of these argument’s “state” changes to “resolved”. Now this is important because it’s treating the resolution of two or more events as one event. For example:

Event-A.completed + Event-B.completed = Event-C.done

So, this $.when() method will return when all of the arguments have a “resolved” state. Since the return value is also a jQuery.deferred object, then we can utilize its .done() method. We pass an anonymous function as an argument to the .when() method. This function will execute when all of the arguments of the .when() method are resolved.

Once we are inside of the anonymous function, we can be confident that our dependencies are loaded. At this point, there are just a couple of things left to do:

- Create our form, using the Mustache.render() method, and inject it into the DOM

- Set up validation using the jQuery.validation plugin

So, here we have it, the end result of all this work we have done, which is a simple one-field form. When you view the full working example (see link below), you can click the submit button to see the validation fail, which will cause the error message to show. And the label for the name field, the submit button’s text and the error message have all been supplied by the “data” variable in our code, which if you remember, is an object literal that contained all of those string values.

Example # 6

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 |

<!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <title>HTML5 Template</title> <script type="text/javascript" src="http://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.7.1/jquery.min.js"></script> <style> body{font: 12px Arial;} form div{margin-bottom: 5px;} label{display:block;font-weight:bold;} input,{width:100%;padding:4px;border-radius:2px;border:1px solid #999;} #container {width:600px;margin:50px auto 0;padding:22px;background-color:#ededed;border:1px solid #ccc;-webkit-border-radius:05px;-moz-border-radius:05px;border-radius:05px;} .val-box{color:red;} .val-message{display:none;} input.alert.error{border:1px solid red;} </style> </head> <body> <div id="container"> <h1>jQuery.when() Example</h1> <h2>Complex multiple script dependency management</h2> </div> <script> var mustacheJsUrl = 'https://raw.github.com/janl/mustache.js/master/mustache.js', jqformValUrl = 'https://raw.github.com/sdellow/jQuery-Form-Validation/master/jquery.form-validation.js', data = { fieldName: "first_name", label: "First Name", submit: "Submit this form", error: "Please be sure to enter your first name" }, template = '' + '<form id="testform">' + '<div class="field">' + '<label for="{{fieldName}}">{{label}}</label>' + '<input type="text" id="{{fieldName}}" name="{{fieldName}}" class="required">' + '<button type="submit">{{submit}}</button>' + '<div class="val-message">{{error}}</div>' + '</div>' + '</form>', confirmFormVal = function (){ //is jquery.form-validation.js loaded on this page? if(!jQuery.fn.formval){ //if not, load it return $.when($.getScript(jqformValUrl)); } else { //it's loaded, just return the resolved jQuery deferred object console.log('formval is already loaded...'); return jQuery.Deferred().resolve();; }; }, confirmMustacheJs = function (){ //is mustache.js loaded on this page? if(!window.Mustache || !window.Mustache || !window.Mustache.name === 'mustache.js'){ //if not, load it return $.when($.getScript(mustacheJsUrl)); } else { //it's loaded, just return the resolved jQuery deferred object console.log('Mustache is already loaded...'); return jQuery.Deferred().resolve(); }; }, formValIsLoaded = confirmFormVal(), mustacheIsLoaded = confirmMustacheJs(); $.when(formValIsLoaded,mustacheIsLoaded).done(function(){ //build the markup fom the template (uses Mustache.js) var form = Mustache.render(template,data); //inject the form $('#container').append(form); //setup the form for validation (form validation plugin) $('#testform').formval(); }); </script> </body> </html> |

In Example # 6, we have the full code for our working example.

Here is the JsFiddle.net link for our full working example: http://jsfiddle.net/Ebj4v/5/

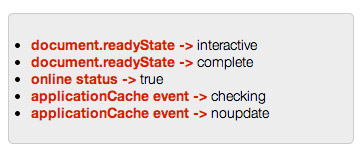

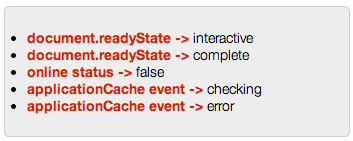

Final Proof of Concept

In the links that follow, we have added script tags to the code. In the first two cases, one of our dependencies is pre-loaded. In the third case both are pre-loaded. Chrome does not like the mimetype of the scripts as they are served from github.com, so please view these examples in FireFox. Open up your JavaScript console when viewing the examples. In each case, you will see a message indicating which dependency was pre-loaded. In all three cases, the resulting behaviour is the same: our code checks to see if a dependency is loaded, if so, great, and if not it loads it.

Both Mustache.js and jQuery.validation plugin preloaded: http://jsfiddle.net/Ebj4v/8/

Summary

In this article we learned how to solve a complex script-loading scenario. In doing so, we discussed the jQuery.deferred() constructor and jQuery.when() methods, learning how they can be leveraged to create an if/else logic so that we can determine whether or not a script was loaded, and then depending on the answer, take the appropriate action.

Helpful Links for jQuery.deferred and jQuery.when

jQuery.deferred

http://api.jquery.com/jQuery.Deferred/

http://api.jquery.com/category/deferred-object/

http://blog.kevinchisholm.com/javascript/jquery/using-the-jquery-promise-interface-to-avoid-the-ajax-pyramid-of-doom/

jQuery.when

http://api.jquery.com/jQuery.when/

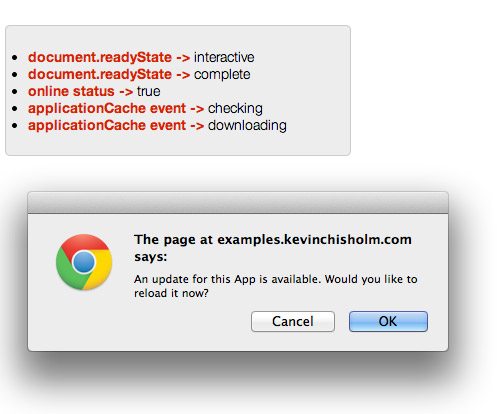

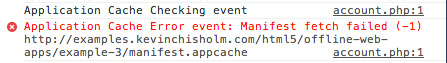

The cache manifest file allows you to easily set up an HTML5 offline application. The applicationCache JavaScript Object allows you to monitor and act upon the events that take place as your app loads.

The cache manifest file allows you to easily set up an HTML5 offline application. The applicationCache JavaScript Object allows you to monitor and act upon the events that take place as your app loads.

It is fairly common for any front-end web developer to examine the query string. If jQuery has taught us anything, that would be the power of abstraction: create functionality once, and then use that functionality as a tool over and over, as needed.

It is fairly common for any front-end web developer to examine the query string. If jQuery has taught us anything, that would be the power of abstraction: create functionality once, and then use that functionality as a tool over and over, as needed. Most front-end developers consume JSON at some point. It has become commonplace nowadays to fetch data from a cross-domain site and present that data in your page. JSON is lightweight, easy to consume and one of the best things to come along in a while.

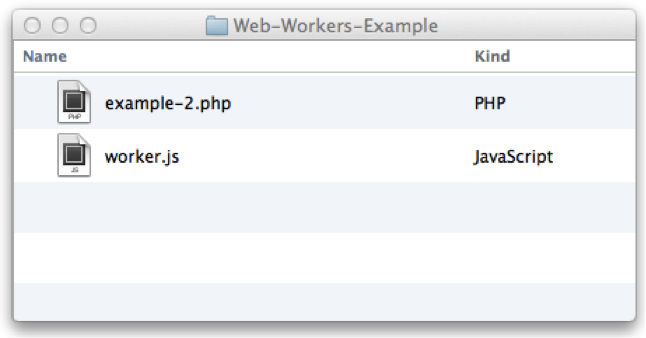

Most front-end developers consume JSON at some point. It has become commonplace nowadays to fetch data from a cross-domain site and present that data in your page. JSON is lightweight, easy to consume and one of the best things to come along in a while. The importScripts() function can be used to load any JavaScript file asynchronously from within a Web Worker, making JSONP a snap.

The importScripts() function can be used to load any JavaScript file asynchronously from within a Web Worker, making JSONP a snap. Learn to master the tricky nature of asynchronous JavaScript with “Async JavaScript – Recipes for Event-Driven Code“. This short yet thorough book explains many concepts which not only demystify the subject, but also arm you with tools to architect smarter solutions.

Learn to master the tricky nature of asynchronous JavaScript with “Async JavaScript – Recipes for Event-Driven Code“. This short yet thorough book explains many concepts which not only demystify the subject, but also arm you with tools to architect smarter solutions.

All the JavaScript you write in the JSFiddle “JavaScript” box gets wrapped in an anonymous function and assigned to the window.onload event of an iframe that is shown when you click the “Run” button.

All the JavaScript you write in the JSFiddle “JavaScript” box gets wrapped in an anonymous function and assigned to the window.onload event of an iframe that is shown when you click the “Run” button.