Mongoose ODM simplifies the process of connecting to your MongoDB database in your Node.js application and working with the data.

Mongoose ODM simplifies the process of connecting to your MongoDB database in your Node.js application and working with the data.

If you are a JavaScript developer, using MongoDB as your backend database is a joy. If for no other reason, you get to think of and interact with data as JSON objects. This serves to solidify the case for Node.js: those of us who live and breathe JavaScript on the client side, can now extend our skill set to include server-side development using the language we love.

The quickest way to get up and running with MongoDB in your Node.js application is to leverage Mongoose ODM. The Mongoose website defines it as a : “…straightforward, schema-based solution to modeling your application data…”. That’s a little deep for me. Suffice it to say, it makes interacting with MongoDB incredibly simple.

In this article, our goal is extremely simple: connect to MongoDB, create a record and then show that record in a web page. While we will barely scratch the surface of what is possible, we will, at minimum, accomplish our modest goal. I’m sure that, as a programmer, you’ll get halfway through this code and realize how much more is possible. You can then take this very basic code, copy and paste it into your own application and then build a more robust solution.

Dependencies

In order to use the code in this article, you’ll need the following installed on your computer:

Installation of these components is beyond the scope of this article, but if you follow the provided links, they will point you in the right direction.

File Structure

For this article, we will need two files: app.js and package.json. In your project folder, create these two blank files. The following sections will explain what to put into them.

Example # 1A

|

|

{ "name": "My-First-MongoDB-App", "version": "0.1.0", "description": "Simple MongoDB example with Mongoose on Node.js", "main": "app.js", "engines" : { "node" : "0.8", "npm" : ">=1.1" }, "author": "Kevin Chisholm", "license": "MIT", "dependencies": { "mongoose": "3.5.7" } } |

In Example # 1A, we have the contents of package.json. I won’t spend too much time on this file. For a more detailed discussion about package.json files you can search this blog for helpful articles. I will point out that the single dependency declared is “mongoose”. When you use node package manager to install dependencies, npm will download version 3.5.7 of mongoose for us.

Example # 1B

In Example # 1B we see the command needed to install the dependencies for our application. In this case, the single dependency declared is “mongoose” version 3.5.7. Once you run this command, you will have everything needed to start writing code.

Getting Started

Open up app.js in your text editor. From this point on, you can copy / paste the code in each example into the app.js (or you can scroll to the bottom of this page and paste the entire code listing in one step).

Example # 2

|

|

//variables we'll need var http = require ("http"), mongoose = require ("mongoose"), dbConnString = "mongodb://localhost/myMongooseDb", dbport = 5000, salesSchema = null,//just a placeholder, we'll overwrite this a bit later salesMember = null,//just a placeholder, we'll overwrite this a bit later salesMemberDocument = null;//just a placeholder, we'll overwrite this a bit later |

In Example # 2 we have the variables that we need for our application. Here are the details:

http : a module built into node.js that provides http server methods

mongoose : will be an instance of mongoose, which we listed as a dependency

dbConnString : tells mongoose where the database is running

dbport : tells mongoose which port to use

salesSchema : will be explained a bit later

salesMember : will be explained a bit later

NOTE: I define salesSchema, salesMember and salesMemberDocument at the top of the script because it is a best practice to define all of your variables at the top of your script or function, even if you are not ready to initialize them.

Example # 3

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

//connect to the database mongoose.connect(dbConnString,function(err, res){ if (err){ console.log ('ERROR connecting to: ' + dbConnString + '! ' + err); } else { console.log ('Successfully connected to: ' + dbConnString); } }); //define the schema to use salesSchema = new mongoose.Schema({ name: { first: String, last: String }, phone: String }); //define the data model, using the schema that we just created salesMember = mongoose.model('Sales', salesSchema); // Clear out old data salesMember.remove({}, function(err) { if (err) { console.log ('There was an error deleting the old data.'); } else { console.log ('Successfully deleted the old data.'); } }); |

Connecting to the MongoDB Database

In Example # 3, we start out by connecting to the database. The first argument is the connection string, which tells mongoose to find the database. The second argument is a function. Because this connection is an asynchronous event, the anonymous function that we pass as the second argument allows us to safely act upon the completed connection event. Like many Node.js callbacks, this anonymous function takes two arguments: “err” and “res” (which you can of course name anything you want). In the callback, we are interested in the error argument. If the error argument is “falsy”, then we can assume it’s safe to proceed. In this case, we simply log the appropriate console messages.

Defining a Schema

Next up, we define our database schema. Again, just to keep things simple, I won’t go into this in detail. Suffice it to say that we are telling mongoose how the data we will work with will be structured.

Defining a Data Model

Now that we have defined our schema, we call the “model” method of the mongoose object, assigning the resulting value to our variable “salesMember”. When calling mongoose.model, we pass the name of the collection as the first argument (i.e. “Sales”). If the collection does not exist, then it will be created. Simple, simple, simple. The second argument is the schema that will be used, which in this case is the variable “salesSchema”.

Finally, we call the “remove” method of our “salesMember” model, which empties out the collection. This will of course delete the data that we are about to create each time you reload the page. You can safely skip this code block so that each time you run the script and create a new entry in the collection, it persists.

Example # 4

|

|

//create a new sales member salesMemberDocument = new salesMember ({ name: { first: Alfred E., last: 'Newman' }, phone: "212-555-1212" }); //save the new user to the database. salesMemberDocument.save(function (err) { if (err) console.log ('Error on save!'); }); |

Creating a Document in the MongoDB Collection

In Example # 4, we finally get down to business. Here we overwrite the “salesMemberDocument” variable with a new instance of the “salesMember” model. We pass it an object which represents the data for MongoDB document (you can think of this as a record in a database table and our “Sales” collection as the database table). We then call the “save” method of the salesMemberDocument object. This persists the data.

Example # 5

|

|

//create a server instance, and start it http.createServer(function (req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'application/json'}); salesMember.find({}).exec(function(err, result) { if (!err) { res.end(JSON.stringify(result, undefined, 2)); } else { res.end('Error in query. ' + err) }; }); }).listen(dbport); |

Starting the Server and Presenting the MongoDB Data

In Example # 5, we create an HTTP server and start it, and then immediately write a “200 ok” header, with the Content-Type of ‘application/json’ (we will present our data as JSON in the browser). Next, we call the find method of the “salesMember” model, passing it an empty object. This tells the “salesMember” model to return everything (i.e. all records in the database table). That method call takes an anonymous function as an argument. We check to see that there were no errors, and if not, we send the result of our find method call to the browser, courtesy of JSON.stringify().

Example # 6

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 |

//variables we'll need var http = require ("http"), mongoose = require ("mongoose"), dbConnString = 'mongodb://localhost/myMongooseDb', dbport = 5000, salesSchema = null,//just a placeholder, we'll overwrite this a bit later salesMember = null;//just a placeholder, we'll overwrite this a bit later //connect to the database mongoose.connect(dbConnString,function(err, res){ if (err){ console.log ("ERROR connecting to: " + dbConnString + "! " + err); } else { console.log ("Successfully connected to: " + dbConnString); } }); //define the schema to use salesSchema = new mongoose.Schema({ name: { first: String, last: String }, phone: String }); //define the data model, using the schema that we just created salesMember = mongoose.model("Sales", salesSchema); // Clear out old data salesMember.remove({}, function(err) { if (err) { console.log ("There was an error deleting the old data."); } else { console.log ("Successfully deleted the old data."); } }); //create a new sales member var salesMemberDocument = new salesMember ({ name: { first: "Gary", last: "Newman" }, phone: "212-555-1212" }); //save the new user to the database. salesMemberDocument.save(function (err) { if (err) console.log ("Error on save!"); }); //create a server instance, and start it http.createServer(function (req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {"Content-Type": "application/json"}); salesMember.find({}).exec(function(err, result) { if (!err) { res.end(JSON.stringify(result, undefined, 2)); } else { res.end("Error in query. " + err) }; }); }).listen(dbport); |

In Example # 6, we have the complete code for our Node.js application. If you paste all of this code into app.js, and be sure that you have successfully executed that file in Node.js, open a browser, and then enter “localhost:5000” in the address bar, you will see the application in action.

Running the Application

In your terminal, navigate to the application folder, and then run the following command:

Example # 7

|

|

[ { "phone": "212-555-1212", "_id": "5234e505674f223908000001", "__v": 0, "name": { "first": "Alfred E.", "last": "Newman" } } ] |

In Example # 7, we have the JSON data returned in the browser. If you followed the instructions in each step of this article, this is what you should see (although the value of “_id” will differ).

Summary

In this article we learned how to use Mongoose ODM to make a connection to a MongoDB database in a Node.js application. We learned how to define mongoose as a dependency and install it with npm (node package manager). We also covered how to connect to the database, instantiate the schema class, and define a model. In addition, we discussed how to create a new document, save it, and then retrieve it. While this article presented the most bare-bones information on the topic, I hope that it has provided the background you need to get started with MongoDB.

Helpful Links for Mongoose ODM and MogoDB

General

MONGOOSE BASICS: STORING DATA WITH NODE.JS AND MONGODB

Mongoose ODM

http://mongoosejs.com/

http://mongoosejs.com/docs/guide.html

https://devcenter.heroku.com/articles/nodejs-mongoose

MogoDB

http://www.mongodb.org/

http://docs.mongodb.org/manual/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MongoDB

http://mrbool.com/course/introduction-to-mongodb/323

There are a few developers who are particularly knowledgeable about JavaScript. In many cases, their work and their writings are real gems that can provide a deeper perspective on the language.

There are a few developers who are particularly knowledgeable about JavaScript. In many cases, their work and their writings are real gems that can provide a deeper perspective on the language. A popular saying in the Real Estate business is: “Location, location, location!” Well, in JavaScript, it’s all about “context”. When you want to leverage the very powerful keyword: “this”, then understanding the current context is critical.

A popular saying in the Real Estate business is: “Location, location, location!” Well, in JavaScript, it’s all about “context”. When you want to leverage the very powerful keyword: “this”, then understanding the current context is critical. Combine multiple JS files into one using JavaScript, Node.js and Grunt.

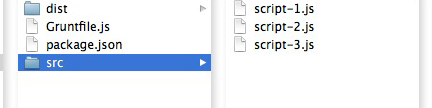

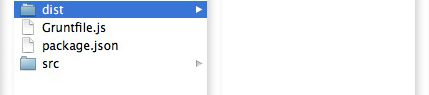

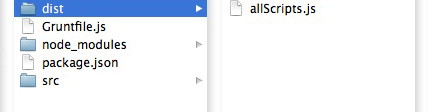

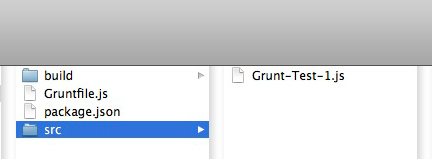

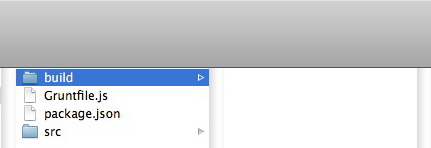

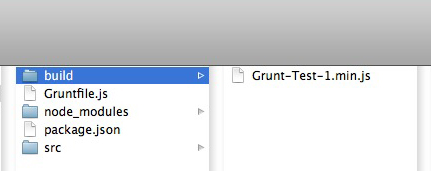

Combine multiple JS files into one using JavaScript, Node.js and Grunt.

By leveraging the Node.js middleware “express”, we can create functionality for viewing, adding or deleting JSON data.

By leveraging the Node.js middleware “express”, we can create functionality for viewing, adding or deleting JSON data. Native JavaScript provides a way to access and manipulate all of the CSS classes that are assigned to an HTML element.

Native JavaScript provides a way to access and manipulate all of the CSS classes that are assigned to an HTML element. Mustache.js provides a simple, yet powerful way to populate one piece of HTML many times with a data set. In this article, we’ll learn how to specify markup that will be rendered when there is an absence of data.

Mustache.js provides a simple, yet powerful way to populate one piece of HTML many times with a data set. In this article, we’ll learn how to specify markup that will be rendered when there is an absence of data. Adding an event listener to your map is much like using the addEventListener() method on a DOM element.

Adding an event listener to your map is much like using the addEventListener() method on a DOM element.