The beauty of creating an HTTP server with Node.js is that you are doing so using a language that you already know: JavaScript.

The beauty of creating an HTTP server with Node.js is that you are doing so using a language that you already know: JavaScript.

If you work with JavaScript, then you’ve probably heard about Node.js. What makes Node.js such an amazing technology is that it turns web-development on its head: a historically client-side language is now being used as a server-side language. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you how insanely cool this is.

When I first started looking at Node.js, my first question was: “Ok, server-side JavaScript. Got it. So what the heck can I do with it?”

Short answer: A lot.

Probably the most obvious and easiest to comprehend application for Node.js is to make a web server. Node handles all the low-level ugliness and let’s you just write code. The code you write is not too much different than the client-side JavaScript that you are used to. The biggest differences come in when you start to realize that you have access to the file system. You can do things with Node that are completely off-limits on the client side. When it comes to creating a simple HTTP server, the amount of code you need to write for proof of concept is amazingly minimal. The examples that follow are very basic. They don’t offer any real-world usefulness, but they do illustrate the small amount of effort needed to get up and running. In Part II of this series, we will look at more realistic HTTP server code for Node.js.

Example # 1 A

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

//step 1) specify that we need the ‘http’ module var http = require('http'); //step 2) start the server http.createServer(function (req, res) { //set an HTTP header of 200 and the meta type res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); //write something to the request and end it res.end('Your node.js server is running on localhost:3000'); }).listen(3000);//step 3) listen for a request on port 3000 |

In Example # 1, we have the absolute bare minimum needed to set up an HTTP web server using Node.js. The very first line tells Node.js that we need to use the “http” module. Using Node’s “require” method, we assign the return value of the “HTTP” module to the variable “http”. This was Step # 1.

(A detailed discussion of the require() method is beyond the scope of this article, but a topic that plays an important role in Node.js. If you are not familiar with the Modules/AsynchronousDefinition proposal from Common.js, I highly recommend reading up on that topic. For any client or server-side JavaScript developer, it’s a biggie.)

The only part that might seem a bit confusing to some is the callback that is passed into the createServer() method. This callback is executed each time the server receives an HTTP request.

For Step # 2, we call the createServer() method of the http object. We pass that method an anonymous function which takes two arguments: the request object and the response object. Inside of that anonymous function, we use the writeHead() method of the response object, to set the server’s response of “200 ok” to the client’s browser, and set the header of “Content-type” to “text/plain”. Next, we call the end() method of the response object. The end() method closes the response to the client. It can also send output to the client. We pass in a string as an argument in this example, and that string is sent to the client’s browser.

For Step # 3, we call the listen() method on the return value of the createServer() method. We pass in “3000”, which tells Node.js to listen on port # 3000.

If you run this code in Node.js, and then in your browser, “type localhost:3000”, you will see the following in your browser: “Your node.js server is running on localhost:3000.”

Whew! The explanation for Example # 1A took much longer to write than the actual code!

As you can see, it’s pretty easy to create an HTTP server with Node.js. In my opinion, the only part that might seem a bit confusing to some is the callback that is passed into the createServer() method. This callback is executed each time the server receives an HTTP request. It might make things easier to understand if we move the guts of that callback to its own function, and then pass that function declaration as the callback to the createServer() method.

Example # 1 B

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

var http = require('http'); function requestHandler(req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); res.end('This request was handled by the requestHandler() function'); } http.createServer(requestHandler).listen(3000); |

In Example # 1B, we create a function declaration named requestHandler. Then we pass that function as the sole argument to the createServer() method. I believe that if you are new to Node.js, you’ll find it is easier to see what is going on, because the createServer() method is all on one line.

Example # 1 C

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

//a helper function to handle HTTP requests function requestHandler(req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); res.end('This request was handled by the requestHandler() function'); } //step 1) require the http module var http = require('http'); //step 2) create the server http.createServer(requestHandler) //step 3) listen for an HTTP request on port 3000 .listen(3000); |

In Example # 1C, we’ve refactored our code to make things even simpler. First, our helper function processes the HTTP request, then Step 1, Step 2 and Step 3. Bing, Bang, Boom. Simple stuff.

Example # 2 A

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

var http = require('http'); function requestHandler(req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); res.end('<h1>My First Node.js Web Server</h1><p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</p>'); } http.createServer(requestHandler).listen(3000); |

In Example # 2A, we’ve upgraded our message to the client’s browser to include some HTML. After all, HTML is what we will really want to serve, right? The only problem is that Node is not parsing the HTML. When you run this example in your browser, you see the HTML tags in the response. That is not what we want. What is happening?

The problem is in the header that we are setting with the res.writeHead() method call. The value of the “Content-Type” header is “text/plain”. So, Node just passes all the text along as… well, plain old text.

Example # 2 B

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

var http = require('http'); function requestHandler(req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/html'}); res.end('<h1>My First Node.js Web Server</h1><p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.</p>'); } http.createServer(requestHandler).listen(3000); |

In Example # 2B, we have changed the value of the “Content-Type” header to “text/html”. If you run this example in your browser, you will see that Node sends the string as HTML, so our H1 and UL elements are rendering as they should in the browser.

Example # 3

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

var http = require('http'); function requestHandler(req, res) { //write the HTTP header res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/html'}); //here is our page header res.write('<h1>My First Node.js Web Server</h1>'); //open the unordered list res.write('<ul>'); //print ten <li> elements to the page for(var i = 0; i <= 10; i++){ res.write('<li>' + i + '</li>'); }; //close the unordered list res.write('</ul>'); //close the response res.end(); } http.createServer(requestHandler).listen(3000); |

In Example # 3, we take things a bit further. Up until now, we have been using the res.end() method to do two things: send some text or HTML to the client’s browser, and then close the response. In this example, we use the res.write() method to send our HTML to the client’s browser, and the end() method is used only to close the request.

We’ve also introduced some logic into our code. While what this example accomplishes is very little, and has virtually no real-world value, it demonstrates that while we have created an HTTP server, we have done so with JavaScript, and we already know the JavaScript language. So, we can do something like create a for/loop block, and use that loop to provide some dynamic HTML output. Again, this “dynamic” aspect of our code is not very impressive, but I think you get the point: it’s just JavaScript, so the sky’s the limit.

Summary

In this article, we learned how to create a simple HTTP server using Node.JS. We covered the three most basic steps needed, which include requiring the HTTP module, calling the createServer() method, and then telling the server to listen for an HTTP request. Finally, we learned how the server executes a callback function for each HTTP request it receives, and the most basic things that need to happen inside of that callback.

Helpful Links for creating a simple Node.js HTTP Server

http://docs.nodejitsu.com/articles/HTTP/servers/how-to-create-a-HTTP-server

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jo_B4LTHi3I

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/6084360/node-js-as-a-simple-web-server

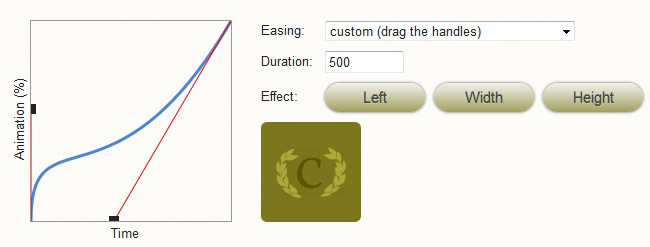

Gracefully handling corner cases is the key to writing more robust, error-free JavaScript.

Gracefully handling corner cases is the key to writing more robust, error-free JavaScript. In parts I and part II of this series

In parts I and part II of this series  In the previous article:

In the previous article:

Decent programmers tests their code before deploying it. In JavaScript development, this usually means viewing the web page that your code interacts with, and clicking one or more elements in the page to ensure that the desired result is achieved

Decent programmers tests their code before deploying it. In JavaScript development, this usually means viewing the web page that your code interacts with, and clicking one or more elements in the page to ensure that the desired result is achieved

Learn How to Build a Social Media Plugin, Using Require.js and the Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD) Pattern

Learn How to Build a Social Media Plugin, Using Require.js and the Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD) Pattern Nested success callbacks are messy business. The jQuery Promise interface provides a simple and elegant solution.

Nested success callbacks are messy business. The jQuery Promise interface provides a simple and elegant solution. Step beyond the basics, and learn how Require.js modules can return various kind of values, depend on other modules, and keep those dependencies transparent to the outside world

Step beyond the basics, and learn how Require.js modules can return various kind of values, depend on other modules, and keep those dependencies transparent to the outside world jQuery’s two .each() methods are similar in nature, but differ in level of functionality

jQuery’s two .each() methods are similar in nature, but differ in level of functionality Understanding the basic components of an AJAX request / response, and being able to write it all out by hand is an important skill for any JavaScript developer to have.

Understanding the basic components of an AJAX request / response, and being able to write it all out by hand is an important skill for any JavaScript developer to have. Less CSS makes organizing, writing and managing your CSS code a breeze.

Less CSS makes organizing, writing and managing your CSS code a breeze.