By leveraging the Node.js middleware “express”, we can create functionality for viewing, adding or deleting JSON data.

By leveraging the Node.js middleware “express”, we can create functionality for viewing, adding or deleting JSON data.

In a previous article: “Using Mongoose ODM to Connect to MongoDB In Your Node.js Application,” we learned the basics about connecting to a MongoDB database in a Node.js application. Because that article barely skimmed the surface of what is possible, we’ll take a few more baby steps here with our data. And for the sake of brevity, I’ll skim over the Mongoose.js details. If needed, you can refer to the article mentioned above for more details on that.

The goals for this article are:

- Allow the user to view all data in the database

- Allow the user to make a JSONP call to get all data

- Allow the user to add a new name to the Sales database

- Allow the user to delete all data in the database

When completed, this will be far from a robust or production-ready application, but we will, at minimum, learn how to view / add / delete data in our MongoDB database, using clean URLs in the browser.

Dependencies

In order to use the code in this article, you’ll need the following installed on your computer:

Installation of these components is beyond the scope of this article, but if you follow the provided links, you will be pointed in the right direction.

File Structure

- app.js

- package.json

For this article, we will need two files: app.js and package.json. So, in your project folder, create these two empty files. The following sections will explain what to put in them.

Example # 1A

In Example # 1A, we have the contents of package.json. Note that for a more detailed discussion about package.json files you can search this blog for helpful articles. The two dependencies declared are “mongoose” and “express”. When you use node package manager to install dependencies, npm will download and install mongoose and express for us.

Example # 1B

In Example # 1B we see the command needed to install the dependencies for our application. Once you run this command, you will have everything needed to start writing code.

Getting Started

Open app.js in your text editor. From this point on, you can copy / paste the code in each example into the app.js (or you can scroll to the bottom of this page and paste the entire code listing in one step).

Example #2

In Example #2, we declare all of the top-level variables we’ll need in our script. Take note of “app”, which will be used to leverage the express middleware that we listed as a dependency. Also, “initApp”, which is called from the very end of this script. It is used to start the HTTP server.

Example #3

In Example #3, we have our database implementation. The details are identical to those in the previously mentioned article, so we’ll skip over that.

Example #4

In Example #4, we get into something new. If you remember from Example #2, the variable: “app” is an instance of the Express middleware object. We use the .get() method of that object to define what will happen when certain requests are made. When users navigate to the root of our web application, they are presented with a simple message. We accomplish this by passing two arguments to the .get() method: a string representing the requests we want to respond to (i.e. “/”), and an anonymous function. That anonymous function takes two arguments: “req” and “res”, which represent the request that was made, and the response object that we will send back. We use the .end() method of the response object, and pass in the string we want to send to the browser.

The second call to the app.get() method responds to “/json/delete”. It, in turn, calls a function named: utils.deleteAllData(), which will be explained a bit later.

Example #5

In Example #5, we use the app.get() method to respond to the request: “/json”. For this request, we want to show all of the data in the database. We start off by requesting all of the data in the database: salesMember.find({}).exec(). The anonymous function that is passed to the exec() method provides access to an error object (if there is one), and the results of our search. In this case, the result object is JSON, which contains all the data in the database, which we then stringify.

We then use the utils.isJsonCallback() method to determine if the user added a callback function name to the query string. If so, we wrap our database JSON with the named callback. We then deliver the JSON by passing it to the res.end() method.

Example #6

In Example #6, we respond to a request to add a new user to the database (i.e. “/addUser”). If you remember from the top of the script, the variable “url” allows us to leverage the same-named Node.js module, which provides programmatic access to the URL. We then use the “url” object to access the query string for the new user parameters. Once we have that information, we can leverage code that is nearly identical to the previous article, to create a new document in the collection. So just think of this as adding a row to a database table).

Once the new data has been saved, we then end the response with some HTML, informing the user of the successful data addition, and add a link that allows them to view all data or go to the home page.

Example #7

Example #7 contains all of the utility functions used throughout our code:

utils.isJsonCallback : Returns true if a callback name was provided in the query string

utils.getJsonCallbackName : Returns the name of the callback provided in the query string

utils.wrapDataInCallback : Returns the JSON data, wrapped in the callback function

utils.deleteAllData : Deletes all of the data in the database

Note: At the end of Example #7 you will also see a call to initApp(). This simply starts the HTTP server.

Example #8

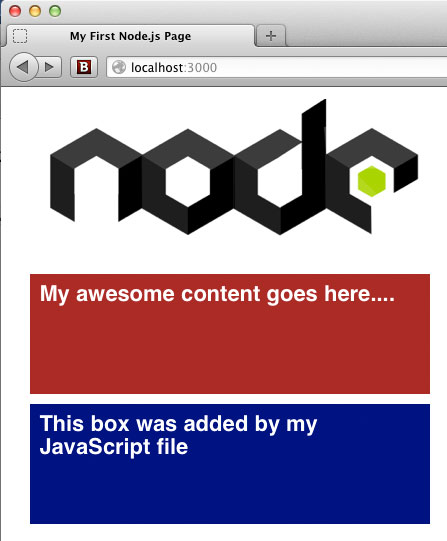

So finally, in Example #8 we have the complete code for our working example. You can start the application by navigating to the root of the folder that contains app.js and entering the following command in the terminal: node app.js.

NOTE: On line # 97 of Example #8, I escape the double quotes that are part of HTML element attributes. I did this only because the color-coding of the plugin used to make code more readable was being particularly difficult for some reason. You will likely need to surround that entire string in single quotes, and remove the escape characters: “\”.

Summary

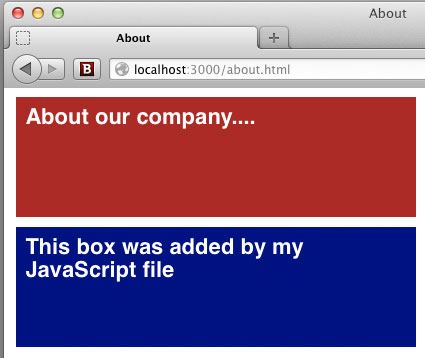

In this article we leverage MongoDB, mongoose and express middleware to create a very basic JSONP API. By using the .get() method of the express object instance, we created functions that respond to specific requests. As a result, we were able to provide the user with functionality to view all data, retrieve all data as a JSONP call, add a user to the database, or delete all data.